David Porter, Fairbank Center Graduate Student Associate, asks how two Russian men ended up in a Qing banner garrison in Guangdong in 1778, and their daring escape plan to return to Russia.

At dawn on April 10 of 1778, two Russian men wearing large straw hats that covered their faces made their way through the streets of Guangzhou’s Eight Banner garrison. As they passed through the Plain Yellow Banner quarter of the city, a patrolman named Huang Tan spotted them and demanded that they explain what they were doing. As soon as they heard his voice, the two Russians dropped the bags they were carrying and took off at a run. Huang Tan and his men pursued them, shouting “stop the bandits!” to rouse the rest of the garrison, and the two Russians were soon captured. Their possessions were searched, and they were found to have been carrying a short musket, 10 ounces of gold, 30 ounces of uncoined silver, 51 silver coins, a small knife, and some rice, flour, and bread.

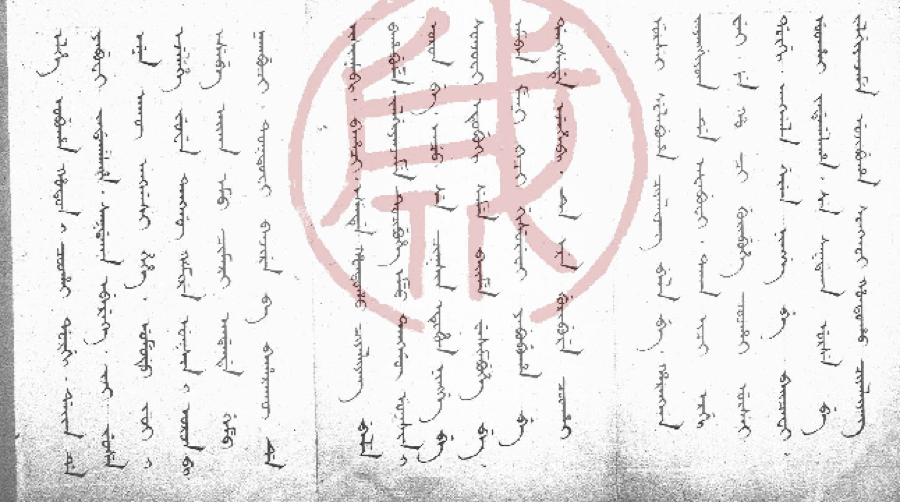

What were two Russians doing in an eighteenth century Qing banner garrison in the far south of China? Why were they carrying so much money and food, and why were they armed? The answers to these questions are found in a Manchu-language memorial sent to the Qing court by Guangzhou garrison general Yong-wei two weeks after their capture. Yong-wei’s memorial offers both a compelling tale of an unusual adventure and a surprising account of late eighteenth century Qing administration.

The two Russians were a 60 year-old man named Dmitri and his son, 28 year-old Yakov. About three years earlier, the two had been fishing along the Irtysh River, which flows from the northwestern part of present day Xinjiang into Kazakhstan before joining the Ob River in Russian Siberia. Whether inadvertently or due to a lack of respect for the border between the Qing and Russian empires, the two men had entered Qing territory and been captured by Qing border guards. The Qing court decided neither to return the men to Russia nor to subject them to formal judicial punishment, but rather to send them to Guangzhou, the furthest corner of the empire from where they had been captured, and have them serve as soldiers in the city’s banner garrison.

The Eight Banners were the core of the Qing military, founded prior to the empire’s 1644 conquest of China. All Manchus — the group that included the Qing imperial family — were enrolled in the banners, with men serving as soldiers or administrators, and outside employment forbidden. In addition to Manchus, a large number of Mongols and Han who had joined the Qing in its early years held hereditary banner status, in their own separate banner divisions. All banner people, regardless of ethnic background, were guaranteed certain legal privileges, and the Qing state took responsibility for providing them with sufficient economic support, in the form of both silver and grain. Banner garrisons were established across the empire to maintain an imperial military presence in conquered Chinese cities, and it was to one of these garrisons that Dmitri and Yakov were sent.

Why Dmitri and Yakov were made into bannermen is unclear — the document describing the case offers no explanation beyond a special act of imperial favor. Upon their arrival in Guangzhou, Dmitri was made a soldier in a Han banner company and Yakov a soldier in a Manchu banner company — again, no explanation was given for placing them in separate ethnic divisions. Despite avoiding punishment, the two men were not happy with their situation; as they told their interrogators, they couldn’t adjust to the local environment — maybe they were put off by Guangzhou’s heat and humidity — and, perhaps more importantly, were lacking in female companionship. They probably were further isolated by their apparent failure to learn to speak either Manchu or Chinese, revealed by the need to find a translator to carry out their interrogation. (The story of this interpreter, a “Russian” — more likely some sort of Central Asian subject of the Russian empire — named Burawanggi, who spoke both Russian and Chinese, and how he came to be in Guangzhou is, unfortunately, not included in the memorial). So they decided to abscond from the garrison and make their way back to Russia.

They saved up money for more than three years, accumulating more than 300 ounces of silver from their banner salaries. As their day of departure drew near, they exchanged much of this money for gold to lighten their load. They planned to sneak out of the garrison and down to the city’s harbor, where they would hire a boat and take it out to a European ship in the harbor — Guangzhou was the only port in the empire that permitted European trade — whose crew they would pay to take them back to Europe. If this plan failed, they had a back-up; using a musket they had purchased from a stranger, they would make their way overland through the mountains towards Russia, hunting game as they went. Even if they couldn’t find their way back, Yakov said, “it would still be preferable to being here.”

Guangzhou garrison officials treated Dmitri and Yakov’s intended escape with the utmost harshness. Though the two men had been ordinary soldiers, as was made clear by the fact that they had been paid official salaries, officials still worried about the effect that showing leniency toward their escape attempt would have on the criminals who had been sent to the garrison from the western part of the Qing empire to serve as slaves in the garrison (while Han criminals from China proper were usually exiled to far western Xinjiang, criminals, as well as family members of rebels, from Uyghur, Hui, and Oirat Mongol communities in the west were exiled to Guangzhou). So, the garrison’s judicial subprefect was instructed to gather all of the “Russians, Oirats, and Muslims” of Guangzhou and publicly execute Dmitri and Yakov in front of them. The emperor was pleased by this decision, writing “properly done” in red immediately adjacent to the relevant line of the memorial.

The story of Dmitri and Yakov speaks to a variety of issues in Qing history. It shows the attention that the Qing state paid to its border with the Russian empire, treating illicit border crossing as a serious issue — why remove Dmitri and Yakov so far from the border, even while not officially treating them as criminals? Perhaps a fear that they might either be spies or, even if not, that if interrogated by Russian officials, they may have seen enough of Qing territory and border defense to provide valuable intelligence. Moreover, it suggests the flexibility with which the Qing state treated membership in the banners — in addition to their core purpose as the empire’s service elite, the banners could accommodate illegal Russian border crossers or defeated Vietnamese royals (the ruler of the Lê Dynasty, overthrown in 1789, and some of his followers were briefly enrolled in banner companies following their flight to Qing territory). Finally, it is suggestive for how Qing officials viewed Russians; they were seen as similar to Oirat Mongols and Central Asian Muslims — that is, as a people of Inner Asia, not of Europe. Indeed, officials were apparently surprised by Dmitri and Yakov’s plan to return home by sea, and made them explain how they could possibly get back to Russia that way.

David Porter is a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard’s Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, and a Graduate Student Associate at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies.

Read David’s blog post Zhao Quan Adds a Salary: Losing Banner Status in Qing Dynasty Guangzhou also on the Fairbank Center Blog.