Is China taking global leadership away from the US? This is a practical issue of overwhelming importance. It is also a question that can be used as a heuristic device to think about the way the U.S. does national strategy. Most of this provocation is intended as such a heuristic device. These preliminary thoughts from William Overholt, Senior Fellow at Harvard University’s Asia Center, are written in the most provocative way so as to stimulate debate.

The U.S. is losing global leadership. China has a vision of leadership but it is unclear whether it can fulfill that vision.

Why is the U.S. losing global leadership? Not for lack of military or economic power. The causes are multiple.

When there’s little risk of a great war, Americans don’t elect foreign policy experts. Compare Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Eisenhower, Nixon, Kennedy, and Bush Sr., all of whom had extensive foreign policy experience (and were elected partly for that reason), with Bush Jr., Obama, and Trump. Trump is the ultimate caricature of this trend, but he’s still on trend.

When there’s little risk of a great war, American presidents and Congress don’t care much about foreign policy. So they allow the instruments of success to deteriorate.

We won the Cold War by rebuilding the economies of Europe and Japan, and creating a global network of economic development. The military’s vital job was to protect that development. Meanwhile the Soviet Union put everything into the military and went bust. The West’s competitive advantage was economic and diplomatic. The military perpetuated a standoff while the economic/diplomatic strategy matured into victory.

Since the Cold War we’ve been starving our diplomatic service and curtailing our economic programs while building up the military, as if we are trying to imitate the failed Soviet strategy. Again, Trump is the ultimate caricature of this trend, but he’s on trend. The reason for this trend is not strategic calculation, but rather that the military has an enormous lobby with almost unparalleled clout in Congress, whereas the State Department and Agency for International Development do not. In peacetime, including relative peacetime, lobbyists exercise hegemony over strategists.

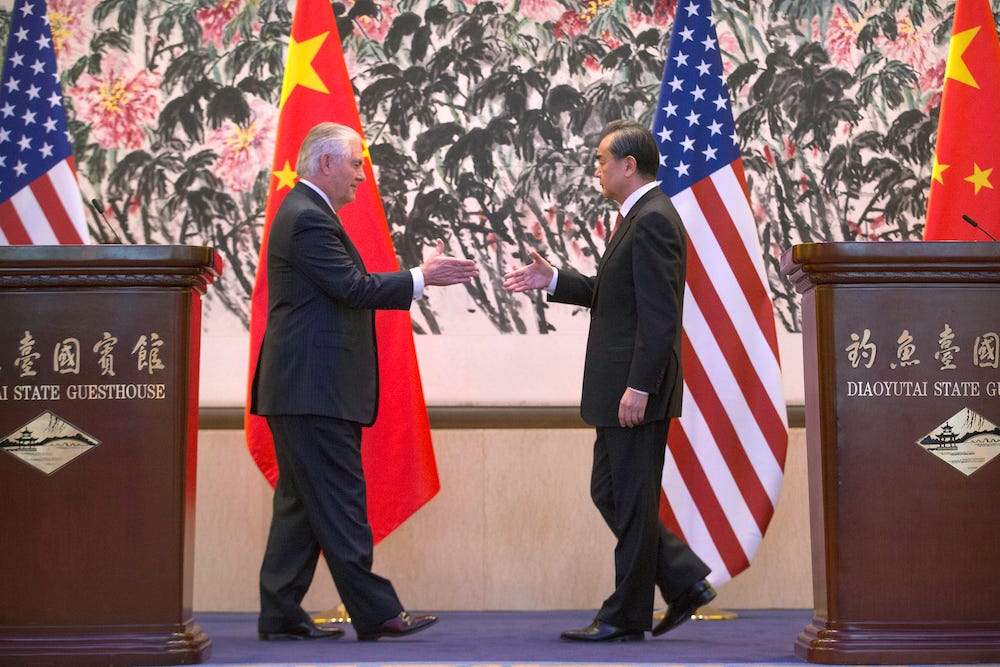

It’s not just budgets. Look at personnel decisions. Hillary Clinton and Rex Tillerson had no experience in foreign policy and had never articulated any novel or insightful foreign policy ideas. Obama appointed more non-career and incompetent ambassadors to higher posts than any previous President. Note particularly his appointments to Japan, arguably now the most important ally: a fund raiser and a political clan leader, each ignorant about both Japan and diplomacy. It’s considered important to appoint the most competent generals and admirals, but diplomacy is for sale.

Many of our great foreign policy leaders were scholars. Look at Kissinger at Brzezinski. Academia no longer produces scholar-leaders like that. Academia has become narrow and siloed. In political science, which used to produce strategic thinkers, an obsession with methodology, particularly regressions, too often takes precedence over substance. Within substance, specialties are ever narrower.

Political scientists mostly have very limited understanding of economics, and economics is crucial to modern strategy. The period after World War II is a watershed in strategic history comparable to the industrial revolution. In the industrial revolution, Britain learned to grow 2 percent per year and as a result created history’s largest empire. After World War II, it became possible to grow economies so quickly (7 to 10 percent for several decades) that a country could become a big power quickly while confining its military to a small share of GDP. And military technology, conventional as well as nuclear, became so destructive that pursuing geopolitical stature by traditional military-territorial means became likely to lead at best to Pyrrhic victories. Just as political scientists have misunderstood the overwhelming importance of economics in the Cold War outcome, they have largely missed the postwar transformation of geopolitical game.

Why did Japan become a big power? Because of its economic dynamism, even without much of a military. Why did South Korea move from inferiority compared with North Korea to towering supeiority? Because its leaders cut back the military and focused resources on economic growth. How did Indonesia go from sick man of Southeast Asia to leader? By abandoning Sukarno’s vast territorial claims and focusing on economic development. Why did China become a big power? Because of its economic dynamism, fueled partly by an early cut of the military budget from 16 percent of GDP to 3 percent, which made it a big power long before it began its military buildup.

Prominent political scientists like Mearsheimer and Allison keep referring back to sixteen or so cases from the time when economic dynamism as a core national strategy was not even foreseen as a possibility. That can’t explain a new world in which the structure of the geopolitical game has changed decisively. This makes for futile futurology and invites gratuitously dangerous decisions.

Clausewitz taught that war is an extension of politics by other means. A larger strategic calculation defined the goals and chose war or some other means to achieve them. Through a combination of lobbyist-induced degradation of diplomatic and economic tools and political science-induced misunderstanding of the post-World War II geopolitical game, U.S. national strategy is gradually being reduced to military tactics. That’s backwards. As a general quoted by Senator Tim Kaine says, “We have Oplans (operational plans), but no strategy.”

The reversal of means and ends in national strategy has a peculiar analogue in the reversal of means and ends in academic political science. Overemphasis on methodology too often conveys to budding political scientists that their job is find things to run regressions on. A limited tool overwhelms the ends. That is not the way science or strategy works. Einstein developed an overarching theory, general relativity, and methodologists spent a century discovering new methods to test it. Strategy, an integrative concept not reducible to any single discipline or method, works that way — and only that way. Have an idea, then find a method to test it.

Contemporary academic silos and methodological fetishes do not preclude strategic thinking, but they impede it.

The strategic weaknesses of government and the problems of academia converge. Government no longer reaches out to academia the way it did in the Cold War. For instance, nuclear strategy was a national project, with government engaging the think tanks, led by RAND, and the great universities. It pulled from many disciplines. Herman Kahn, the great nuclear strategist, was a mathematical physicist. Tom Schelling, who brought game theory to nuclear strategy, was a Nobel Prize-winning economist. Most of the leading nuclear strategists worked outside government. All of them played roles defined by strategic thinkers like Eisenhower who, knowing that the stabilization of Western Europe and Japan through economic development was vital, kept the military and its budget under higher control.

Contrast what has happened with cyberwar, which is the 21st century counterpart of nuclear weapons. Have our top leaders thought deeply about strategies in the age of cyberwar? Have they taken a long view? Have they reached out and engaged the best minds? Has there been a national debate? No.

Cyberwar is the one area of warfare where the U.S. faces potential equal powers. In nuclear and conventional war, the U.S. dominates the globe — and will for the foreseeable future. But in cyberwar China, Russia, India, Iran and Israel are potential equals. So it is in the overwhelming interest of the U.S. to quarantine this kind of warfare, as we did with nuclear weapons. Instead, we’ve diddled with it tactically, for instance to collaborate with the Israelis in momentarily disrupting Iranian nuclear fuel purification. That’s about as strategically counterproductive as it would have been to use nuclear weapons in Vietnam, but contemporary leaders don’t think strategically so they allow tactics to defeat larger strategic interests. In consequence, we may well find ourselves at greater risk from cyber than from nuclear.

Just as government employs academia less, conversely academia has become more of a guild, usually rejecting those with extensive experience in government or business. Today’s students rarely experience the thrills provided to my generation by the lectures of Reischauer and Fairbank with their grounding in experience.

As a result of all this, U.S. strategic thought has failed to address two of the four most decisive strategic developments of the post-World War II era: the shift in geopolitical structure to favor economics-focused strategies and the emergence of cyberwar. It has addressed nuclear strategy with considerable success. It has at least engaged in a great debate about the fourth great issue, climate change, although science deniers have (temporarily?) stymied implementation of a serious U.S. strategy. Overall, this is a recipe for accelerating loss of U.S. global stature despite continuing military and technological superiority.

What about China?

China has key advantages. Chinese leaders think strategically and long-term. Deng Xiaoping enunciated a 50-year view for Hong Kong and Taiwan. China now has a 50-year environmental plan. Chinese leaders think a decade or three ahead in planning infrastructure. China’s long-term strategies for urbanization, notwithstanding see-through buildings and some ghost cities, make the difference between Shanghai and Mumbai. Long-range strategic thinking is a principal reason why their economy is so successful and it is why they have, for instance, successfully turned the colonial Hong Kong transition from a dangerous potential conflict into a huge economic advantage.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a strategic vision exactly parallel to the Roosevelt-Truman-Eisenhower vision that dominated the second half of the 20th century. The vision is compelling for the same reasons that the U.S. vision was.

The Chinese have fundamental problems, however, that could impede their efforts at global leadership.

Their reach may exceed their grasp. They are in a period of hubris, where they are committing to vast expenditures in many areas at a time of slowing growth and financial squeeze. So far, a diminished pace of economic reform seems insufficient to fuel and fund China’s grandiose ambitions. Slow reform may mean that resources devoted to a grand vision become wasted.

China doesn’t have allies, except Pakistan, dangerous and unstable, and North Korea, an enemy that Beijing feels it must treat as an ally. While China’s economic and rising military power rightly impress, Beijing has not been able so far to leverage that into an effective network of allies and friends. Tactical excursions into disputed maritime areas and the disputed Indian border put China’s long-term geopolitical strategy at risk.

Likewise, tactical leadership needs for interest group support, particularly from the state enterprises (SOEs), put China’s grand economic strategy at risk. Tactical efforts to gain special advantages for China’s SOEs seem to contradict the vision of an open global economy.

China also lacks effective soft power. Its political system is unattractive, and its efforts to leverage China’s extraordinary cultural heritage into a geopolitical magnet have so far produced limited results.

Until it can overcome these constraints, China’s impressive conceptual leadership and its rising influence over its neighbors will not translate into global geopolitical leadership.

Under increasingly provincial politicians, the U.S. is sacrificing global leadership. China’s influence is rising and will continue to rise, but for the foreseeable future neither China nor Japan nor the EU offers much hope for replacing U.S. global leadership. A world without leadership may be temporary but for now that is where we are heading.

William Overholt is a Senior Fellow at Harvard University’s Asia Center, and a former senior research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.