Austin M. Strange, Ph.D. Candidate in Harvard’s Department of Government, where he researches international relations and Chinese foreign policy. Together with a team from AidData and Heidelberg University, Austin has been tracking China’s international aid and state financing, which presents a more complex view of Chinese aid than was previously thought.

Policy makers and pundits have strong opinions about China’s role in international development, including its foreign aid to other countries. New evidence suggests a more complex reality with important consequences for recipient economies and other donors.

A Polarized Discourse on Chinese Foreign Aid

Exaggerated headlines have dominated discussions on Chinese foreign aid for much of the past two decades. For some, China is a “rogue donor” that “couldn’t care less about the long-term well-being of the population of the countries they `aid’.” If not extracting resources for its own economy, Beijing is either busy propping up authoritarian regimes or luring strategically important countries into its orbit through predatory financing.

For others, rather than a pariah, China is a paradigm for modern development finance. China’s financing — -with “no strings attached” and swift project implementation — -is exactly what developing countries need to jumpstart their economies. As summarized by former Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade in 2009, “China’s approach to our needs is simply better adapted than the slow and sometimes patronising post-colonial approach of European investors, donor organisations and nongovernmental organisations.”

Researchers have long suggested that reality is far more complex. But extreme narratives persist, even at the highest levels of foreign policy decision-making. Most recently, in January 2018 Australian Minister for International Development and the Pacific, Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, asserted that China was building “useless buildings” across Pacific Island states to bolster its regional influence. China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Lu Kang replied, “assistance provided by China has significantly fueled the economic and social development of these countries.”

Part of the problem is incomplete information: China’s government publishes far less detailed information on its aid activities than most other large donors. In addition, efforts to track data on Chinese aid by researchers, while making valuable strides, have often struggled to accurately categorize and measure China’s aid flows.

A Closer Look at the Data

However, the information gap is narrowing. Since late 2011, colleagues at AidData, Heidelberg University, and myself have been tracking aid and other types of state financing from China to other countries. The latest versions of the data and methodology were released in late 2017. Our dataset includes over 4,300 project commitments worth over $350 billion financed by China between 2000 and 2014. Projects are located in 139 countries across Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Central and Eastern Europe. The dataset was created with the Tracking Underreported Financial Flows (TUFF) methodology.

The data demonstrate the pitfalls of slapping singular labels on China’s international development footprint. As others have pointed out, much of China’s official financing is inherently more commercial than developmental. Similarly, our dataset reveals that most of China’s government financing to the developing world is not actually “foreign aid” as defined by Western donors. Less than 25% of China’s official financing resembles “Official Development Assistance” (ODA), or foreign aid in the strict sense.

Failing to distinguish between ODA and other official finance (OOF) from China can lead to highly questionable inferences. For instance, while recent headlines purport that China is poised to overtake the United States as the world’s largest aid donor, in reality American ODA commitments still far outpace ODA from China. In short, while only a fraction of China’s official finance, Chinese ODA is an important resource for many development countries. To avoid comparing “apples and dragon fruits,” it is crucial to separate out China’s foreign aid (i.e. ODA) from other types of Chinese official financing.

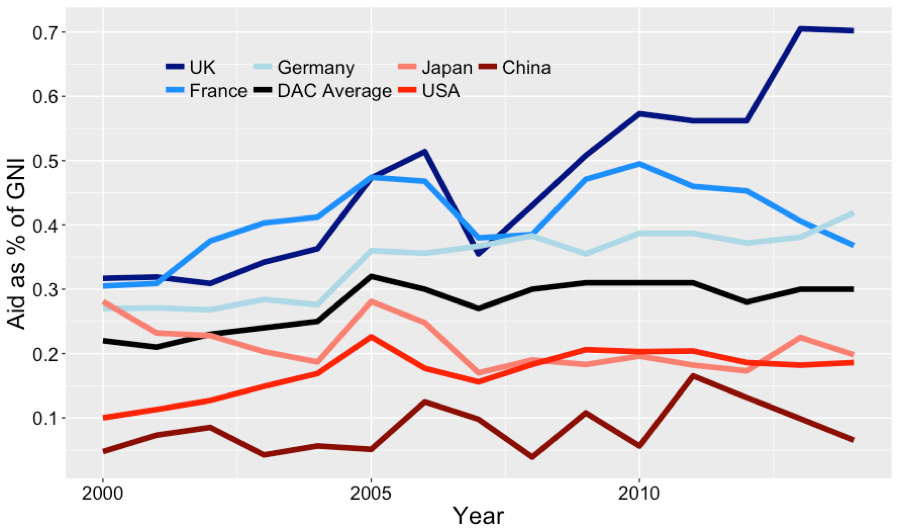

Moreover, compared to other major economies, China invests a relatively smaller share of its economic resources in foreign aid. As Figure 2 illustrates, China’s net ODA — -defined as the ratio of ODA to a donor’s gross national income — -has remained far lower than other major donors, including Japan and the U.S. This is also a tiny fraction compared to the early years of the P.R.C., when foreign aid served as an important instrument for Mao’s revolutionary diplomacy abroad. China’s low net ODA is perhaps not surprising, given the sheer size of China’s economy and the fact that China is still a developing country with its own pressing demands for domestic poverty alleviation.

On the other hand, the 21st-century proliferation of Chinese ODA is somewhat remarkable given that China only became a net foreign aid donor around 2005. Figure 2 illustrates a steady uptick in China’s provision of ODA commitments worldwide since 2000. In 2000 China committed $1.32 billion ODA worldwide, 15th among all donors and behind Switzerland, Spain, Australia and Italy. A decade later, Chinese ODA commitments increased by a magnitude greater than 10 to $13.77 billion, positioning China as the world’s 4th largest donor that year behind only the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany. Overall, China committed 3,159 ODA projects worth $80.66 billion between 2000 and 2014, roughly 60% of which went to Africa. In other words, though only a fraction of China’s official finance, China’s ODA is increasingly significant.

Reasons for Optimism and Concern

Our findings provide reason for optimism as well as concern regarding China’s foreign aid portfolio. On the one hand, the “rogue donor” label appears shaky. Chinese ODA appears no more likely than U.S. aid to flow to resource-rich, corrupt authoritarian countries, and is highly concentrated in the largest and poorest African countries. At least in the short term, there is some evidence that Chinese aid projects boost growth at both nationally and locally. Though China’s ODA does appear designed in part to secure geopolitical influence, the same can be said of aid from Western donors.

On the other hand, researchers have used these new data to uncover worrisome byproducts of China’s aid. Sub nationally, for example, China’s “aid on demand” approach enables African leaders to reroute Chinese aid projects to their home and ethnic regions. Chinese aid may also help fuel local corruption relative to aid projects from the World Bank in Africa.

Beyond ODA, the net impacts of China’s other forms of official finance remain murkier. Some observers view enormous infrastructure investments financed by China’s government as instruments of “debt-trap diplomacy” that create political economic leverage over recipients, while others see China’s loans as essential building blocks of development “hardware” that Western creditors are reluctant to fund. As in the case of ODA, additional careful empirical research is needed to ground these debates, and may reveal that the realities on the ground cannot be aggregated into a single headline.

Moving forward, it is imperative for recipient governments and other development players to better understand the activities of China and other non-Western financiers.While the creation of Chinese-led international institutions has dominated recent headlines about Beijing’s foreign economic policies, China’s leaders continue to recognize the strategic value of bilateral foreign aid. In early 2017, Xi Jinping emphasized that “optimizing the strategic layout” should be an important consideration in China’s aid provision.

Having better data is not a panacea for misperceptions about China’s aid and other foreign policies. Popular commentaries will understandably continue to use provocative claims to grab headlines. The lack of official government data does not help. Yet continuing to add greater precision when conceptualizing and measuring the activities of China and other donors who underreport their official finance is an essential first step.

Austin Strange is a Ph.D. Candidate in Harvard’s Department of Government researching international relations and Chinese foreign policy. His dissertation explores trade policies in Chinese history to shed light on the domestic sources of non-democratic foreign economic policies.