Fairbank Center Graduate Student Associate, Yitzchak Jaffe, talks about his research on cooking during the Western Zhou expansion.

The importance of food and its centrality in Chinese culture, can hardly be overstated. While not always at the forefront of academic research, important scholarship has looked at the development of the Chinese kitchen over the centuries.

The most common approach to studying food preferences in ancient China has been to either document the earliest occurrences and examples of what will eventually be identified as typifying Chinese cuisine (e.g. when does tofu make its debut?), or by tracing later traditions and even modern practices backward, into the past (such as stir-fry cooking methods). In his examination and survey of how foodways developed in China, K.C. Chang stated that it is clear that “continuity vastly outweighs change”.

Yet this certainly cannot be the case and extending the present into the past cannot be the way forward. As Endymion Wilkinson writes in his account of Chinese food history, upon preparing a menu composed of dishes from a sixth century cookbook, his Chinese guests were unwilling to refer to it as ‘authentic’ Chinese food.

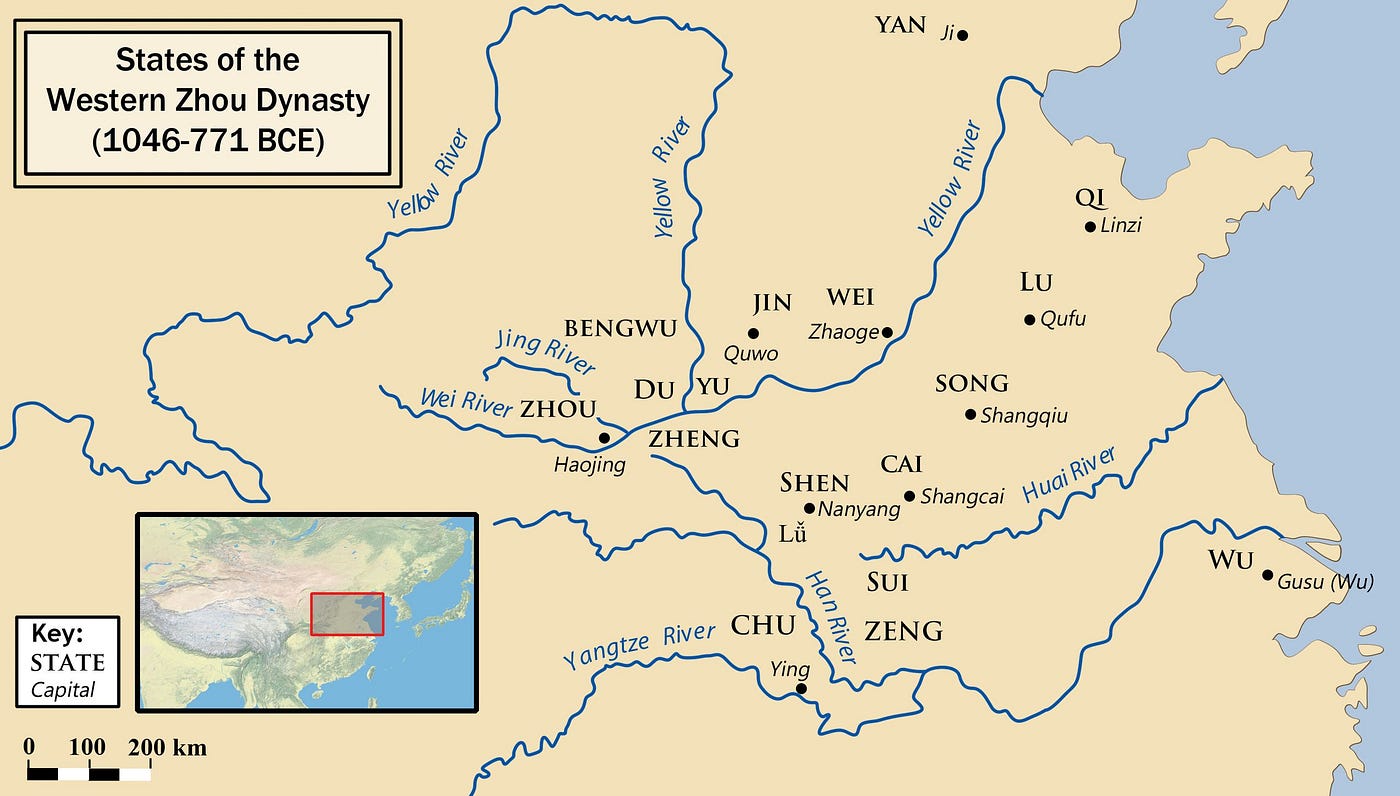

As part of my research, which focuses on observing the results of the Western Zhou (1046–771 BCE) expansion, I examined changes in foodways and the impacts the Zhou had on the peoples they came in contact with. Specifically, I focused on the li 鬲 cooking vessel (see above) in order to examine the way food was made and who it was eaten with. Li vessels are possibly the single most abundant cooking vessel found in ancient Chinese sites.

What was made in them is, however, less clear, but based on archaeobotanical (the study of ancient plant remains) evidence and textual sources, it is feasible that the staple crop of the early inhabitants in northern China was millet. Other vegetables, legumes and meats supplemented this diet, but grains would have constituted the majority of calories consumed.

One possible way these millet grains may have been prepared is by boiling them into gruel, a dish still popular today. In fact the ancient form of the character for porridge zhou 粥 was 鬻 — comprised of porridge and li vessel characters; this is seen by some scholars as good evidence for the practice of making porridge in li vessels.

My study examined the ‘usewear remains’ on the li ceramic vessels: Here the traces of soot as well as internal and external carbonization remains (the byproduct of cooking) on vessel walls are recorded (see figure). As a whole, two main types of cooking can be recorded where: 1) dry modes of cooking, such as roasting and braising (i.e. with little use of liquid or oil), will result in the entire internal part of the vessel to be blackened, while the 2) wet cooking mode, which uses large amounts of water or other liquids (as in soups or stews), will leave only a small band of carbonization just above where the liquid level would have been.

Using this method I examined the li ceramic vessels from four different sites from the area of Linzi in Shandong, two predating the Zhou and two of the Early Zhou period.

The two pre-Zhou sites showed a mix of wet and dry modes and it is possible that different kinds of dishes where served at meals or that two different tradition of cooking millet existed. In contrast at the later Zhou sites, the adherence to the wet cooking mode suggests that little liquid was lost during the cooking process, making for a more watery porridge.

Differences between sites existed as well as the size of li vessels varied: the li of both pre-Zhou sites could cook for no more than three people at one time, while those at the Zhou sites could feed up to ten. It is quite possible that eating parties or even families became larger during the Zhou period and feasting may have been more important as well. At one of the Zhou sites a number of li were big enough to prepare food to serve 25 people at one sitting.

Yitzchak Jaffe is a former Ph.D. Candidate at Harvard University’s Department of Anthropology and Graduate Student Associate at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. He is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at New York University.