Annemieke van den Dool — Visiting Scholar at Harvard Law Schools’ East Asian Legal Studies Program and Ph.D. Fellow at the University of Amsterdam — examines how public health scandals influence China’s laws, and how prepared China is for a new pandemic.

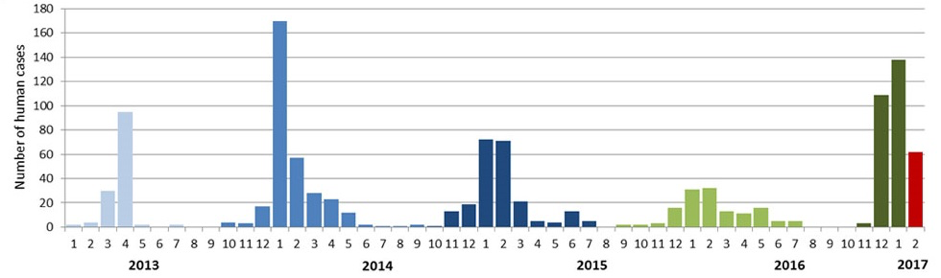

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently issued a notice warning people traveling to China for H7N9 bird flu, an influenza virus that epidemiologists say may cause the next pandemic. Since the H7N9 virus was discovered in Shanghai in March 2013, more than 1,000 people have been infected, 359 of whom died. The virus is most active during spring and winter, especially this winter, with at least 130 cases in 2017, which is more than in previous years.

The H7N9 outbreak brings back memories of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic of 2003 which started in China. Within nine months, more than 8,000 people in 29 countries became infected, with 774 reported deaths. This was partly because China actively suppressed information about the new virus.

The recent upsurge in H7N9 cases raises the question how worried we should be. Has China learned from previous experiences? Is the country prepared to contain the H7N9 virus or is this the start of a new pandemic?

Highly lethal but no person-to-person spread

The good news is that, contrary to SARS, there is no evidence of sustained person-to-person infection. The bad news is that the death rate of H7N9 patients is very high. On average, 40% of patients die, compared to seven percent for SARS. Moreover, H7N9 spreads silently amongst poultry, without animals showing signs of sickness. This means that, if birds are not tested before they are sold on markets, the virus can be transported from farms to markets where it can infect workers and costumers.

More transparency since SARS

Secrecy was a major reason why so many people were infected with and died of SARS. In 2003, existing regulation stipulated that large scale epidemics were state secrets until officially announced. News media were not allowed to report on epidemic outbreaks unless it had already been announced or such reports had been approved.

SARS turned things around through a string of new laws and rules. With the SARS crisis still ongoing, premier Wen Jiabao signed the Regulations on Emergency Response to Public Health Incidents (突发公共卫生事件应急条例 tufa gonggong weisheng shijian yingji tiaoli,) which, amongst other things, made it mandatory for the government to provide information about epidemic outbreaks to the general public.

The obligation of the government to provide information about epidemic outbreaks was also included in article 38 of the 2004 amendment of the Infectious Diseases Law (传染病防治法 chuanranbing fangzhi fa). Lawmakers openly acknowledged that SARS had raised a number of issues, including “…impeded communication channels for reporting and circulating information about epidemic situations…”

The trend towards more transparency continued with the removal of a controversial article from the draft State Emergency Law, which sanctioned news media for releasing information about an emergency without prior authorization and for falsely reporting a situation. It was voted into law in 2007. The effect of SARS even reached beyond the emergency and disease arena by accelerating the making of the Government Information Openness Regulations (政府信息公开条例 zhengfu xinxi gongkai tiaooli) which finally came into force in 2008.

Reasons to worry: Decreasing transparency and live poultry trade

Despite the legal change brought about by SARS in terms of transparency, the question is how these rules will work out in practice over time. When the first cases of H7N9 appeared in 2013, China was generally praised for its response. As such, it is easy to forget that authorities in China initially denied the emergence of this new virus and did not release information until four weeks after the first H7N9 patient died. Moreover, whereas in 2013 China’s Center for Disease Prevention and Control shared updates almost daily, nowadays there is a much larger time lag between diagnosis and public announcement. Information is also less detailed than before.

In addition to unstable reporting, another major issue is China’s management of the live poultry trade, which is the main source of H7N9 infections. Research has shown that closure of live poultry markets is a very effective way to prevent infections. However, they are not permanently closed due to their economic and cultural importance. Moreover, there is not yet an alternative for live poultry in the form of a frozen poultry meat supply chain.

Some cities are working on solutions though. Cities in Guangdong and Zhejiang have started to implement a mandatory system of “concentrated slaughtering, cold chain distribution, and fresh on the market.” This means that instead of picking a live chicken on the market that is slaughtered on the spot, consumers can only buy poultry that is already slaughtered. Although this has great potential in terms of containing the spread of the H7N9 virus, for it to have the best effect it is important that programs are implemented nationwide within a very short time frame.

Consolidation of lessons learned helps prevent pandemic

With (local) health authorities in China now publicly announcing new cases of H7N9, there is certainly more transparency in the country than a decade ago, albeit less comprehensive and timely than during the first H7N9 wave in 2013. Likewise, things are moving in the right direction with regard to the management of live poultry trade, yet China requires a nationwide approach towards this topic to contain the spread of H7N9 and other avian influenza viruses. The question is whether China needs another pandemic to consolidate its policies on infectious diseases or whether it will act proactively now by enforcing its transparency policies and by implementing a ban — or serious restrictions — on live poultry trade.

Annemieke van den Dool is a Visiting Scholar at Harvard Law Schools’ East Asian Legal Studies Program and a Ph.D. Fellow at the University of Amsterdam.