Lu Kou, Ph.D. Candidate at Harvard University, describes how sixth-century diplomats were expected to be apt at verbal confrontation and witty rebuttals to achieve their diplomatic missions.

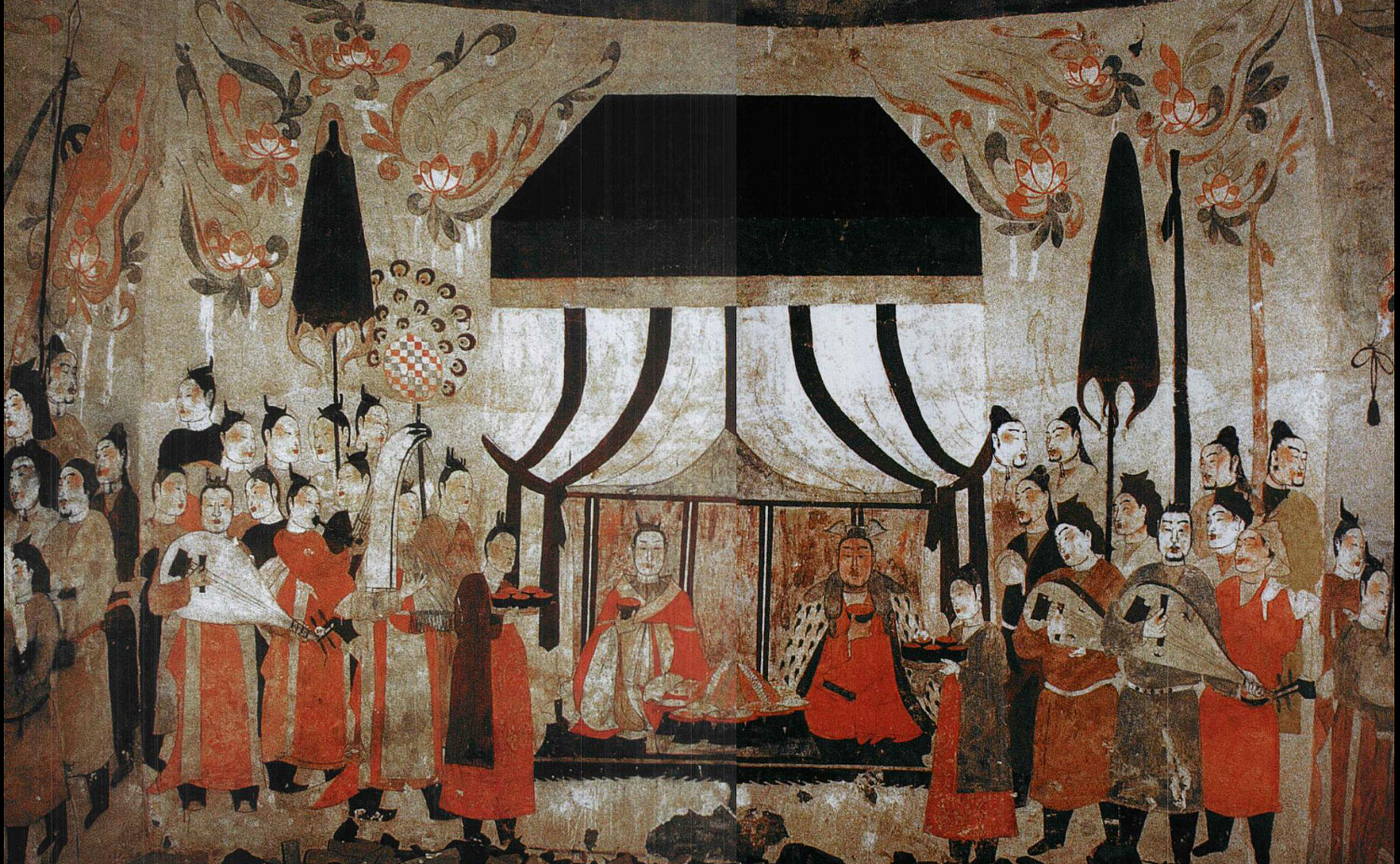

Early medieval China, also known as the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589), was a period of political division when several rival states fought for dominance. Royal envoys were frequently dispatched by court centers for interstate notification and communication, and they carried out a variety of crucial diplomatic tasks, such as arranging marriage alliances, negotiating territorial boundaries, and facilitating the release of hostages.

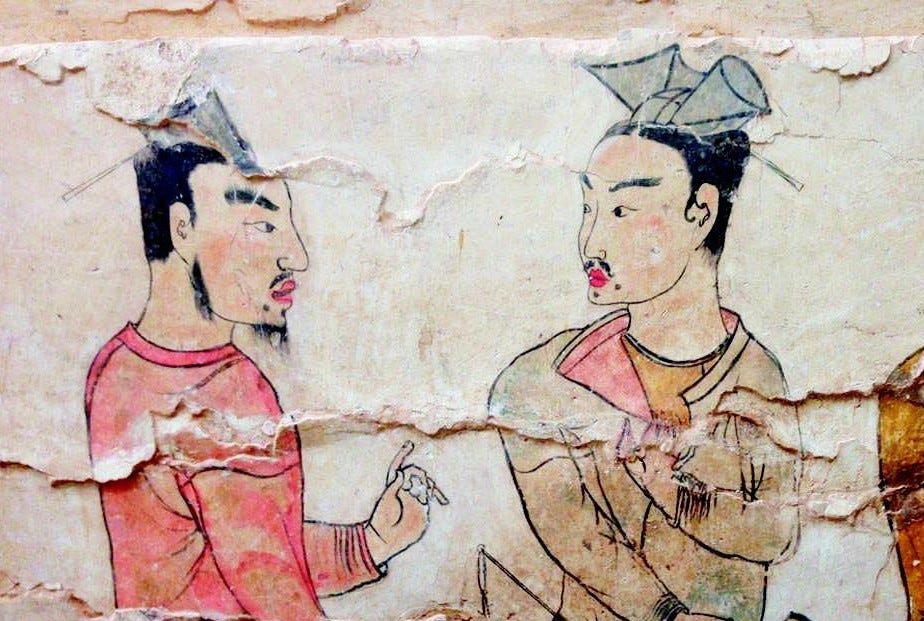

Even though emissaries often bore tokens of peace and aimed for reconciliation, hostility between states never disappeared; rather, it was channeled into the verbal realm. Verbal hostilities permeated every facet of a diplomatic journey, affecting matters as serious as debates on dynastic transitions and as “trivial” as conversations over the dinner table on local weather or food. Envoys and hosts often engaged in “discursive battles.”

During these occasions, state legitimacy, regional customs, and ethnic traits became contentious grounds in need of explanation and justification. State representatives were expected to adequately address hostile comments and offer clever rebuttals to defend themselves and the honor of their states.

One example can aptly illustrate the verbal confrontation between diplomatic representatives.

Xu Ling (507–583) was a courtier from the Liang dynasty (502–557), one of the southern dynasties, who came to the north in the 540s on a diplomatic mission. Wei Shou (507–572) was his host. It was unbearably hot on the day Xu was received, and Wei Shou aimed a mocking comment at him:

“The hot weather today must have been brought here by you, Palace Attendant Mister Xu.”

Wei’s insult, while light-hearted, operated on a geopolitical and cosmological level. The elite at the time — no matter which state they served — were all familiar with the established discourse about the cultural center and its relation to peripheries. It was commonly believed that the center featured the most moderate climate and was most suitable for the development of civilization, while the four peripheries were uninhabitable in part because of their extreme weather, in addition to the presence of monsters and barbarians. Wei Shou implied that the northern state, currently occupying China’s heartland, normally enjoyed pleasant weather; but that the envoys, coming from the southern periphery, had brought intolerable heat and caused this imbalance.

To address Wei’s unfriendly comment, Xu Ling responded:

“In the past, after Wang Su [464–501] came to your domain, he helped the Wei dynasty [i.e., the northern state] establish ritual protocols and regulations. Now I have come as an envoy to make you, sir, understand the difference between hot and cold.”

Wang Su was a southern courtier from the prestigious Wang clan who defected to the northern state sixty years prior to Xu Ling’s visit. As a learned man, Wang had been treated with respect by northern emperors, who entrusted him to rectify rituals and develop cultural innovations for the Wei state. Xu Ling’s comment thus created a cultural lineage that treated southerners as teachers of cultural refinement and portrayed the northern dynasty as the receiver of civilizing influence. In addition, rituals are about making proper distinctions. According to Xu Ling, his arrival would help Wei Shou further understand the basic vocabulary that humans use to describe the natural world. His response transformed the harmonious central land imagined by Wei Shou into a primitive land where the inhabitants were too “barbaric” to grasp and articulate the proper distinction between “hot” and “cold.” This story ends with the northern host, unable to come up with an answer, feeling ashamed.

Verbal negotiations like this are evidence of a shared cultural legacy of both the northern and southern states and a consensus on the importance of effectively appropriating and interpreting that legacy for larger claims. They also demonstrate the crucial functions of rhetoric in asserting state legitimacy and shaping people’s perception of political reality. The articulateness of the envoy was so vital to the state during this period of division that one of the civil service examination questions given by the ruler in the southern court in the late fifth century was about how to select a competent diplomat:

“[The emperor asked:] We hope to make use of rhetoric and eloquence instead of relying on weapons [for conquest]. As for [the one who could] conquer the northern capital with a few words, and pacify the [northern] five prefectures with one expression, what are the means to achieve this? Who can be appointed?”

As rhetoric is directly connected to political conquest, the conversations between envoys and their hosts became metaphorical “battlegrounds” where outmaneuvering the rival during rounds of verbal exchange was as important as winning combat in the field. Hence state authority and legitimacy very much depended on rhetorical manipulation and the effectiveness of verbal persuasion.

One last comment about the sources. This anecdote about Xu Ling and Wei Shou (and the latter’s “humiliation”) is found in the History of the Chen Dynasty, a historical record compiled by southerners, even though Wei Shou, a famous historian himself, also compiled a History of the Wei Dynasty in which many instances of northern envoys’ verbal victory were recorded. This discrepancy alerts us that historiographical mediations also played a crucial part in filtering information according to different agendas and representing contrasting versions of “reality” sanctioned by rival court centers.

Lu Kou 寇陆 is a Ph.D. Candidate at Harvard University’s Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. He is currently a Graduate Student Associate at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, where he is completing his dissertation entitled “Courtly Exchange and the Rhetoric of Legitimacy in Early Medieval China.”

Interested in Early Medieval China? Read Lu Kou’s other blog post on “Improvising Poetry in China’s Medieval Court.”