David Porter, Ph.D. Candidate and Fairbank Center Graduate Student Associate, describes Zhao Quan’s unsuccessful attempts to earn money from banner status in the Qing Dynasty.

One day in early 1813, a 20 year-old Manchu cavalryman named Quanheng hurried to the yamen of his commander to confess to a crime. He was, he explained, not really a Manchu, but had instead been adopted as an infant by a Manchu bannerman named Hequan. In reality, he was the natural-born son of a commoner named Zhao Quan, who had convinced Hequan to adopt Quanheng in the hopes that the boy would eventually receive an official salary which could be split between his real and adopted fathers to help support them in their later years. In 1813, Quanheng had finally obtained a post in the cavalry. When Hequan refused to share his adopted son’s new salary with Zhao Quan, Zhao went to Quanheng, who had never known he was adopted, and told him everything. Fearing that he might be implicated in the crime — illegally receiving a banner salary was a very serious offense — Quanheng immediately made his way to the yamen to report his fathers’ misdeeds.

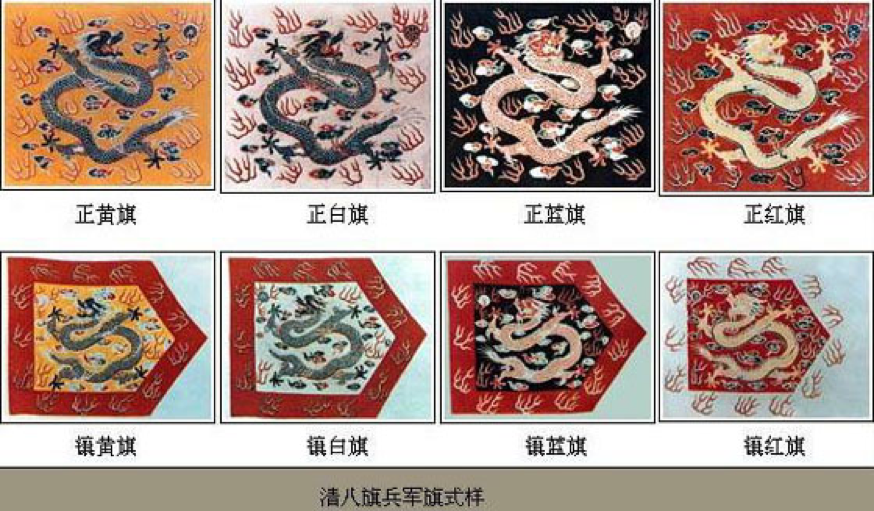

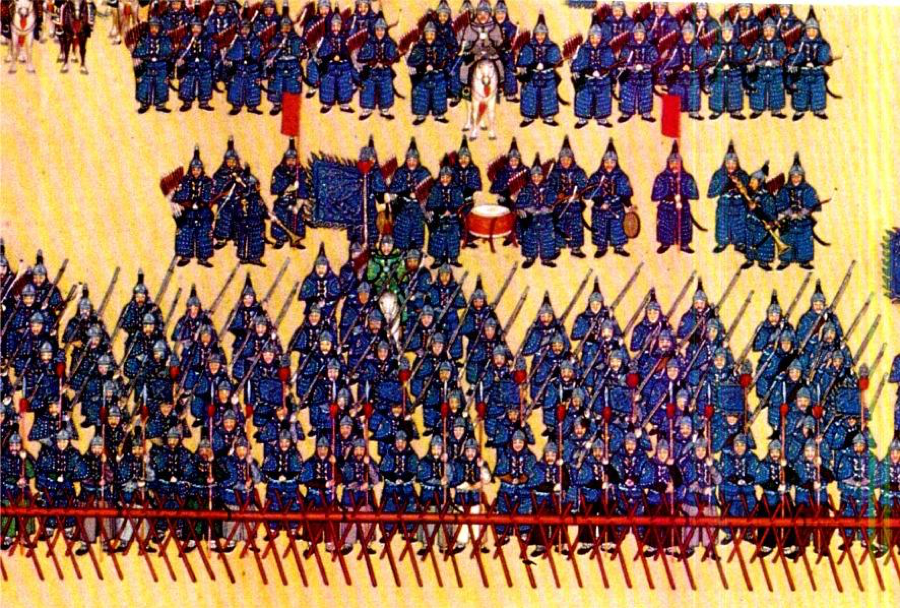

To make sense of the crime that Quanheng reported, it is first necessary to understand a bit about the status system in China during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). The bulwark of the Qing military was the Eight Banners. Named for the eight differently colored flags associated with each division, the Eight Banners did not merely include military men. Rather, the entire families of every banner soldier were officially registered as banner people, a fully heritable status. Every Manchu man, woman, and child was supposed to be included in the banners, largely as a result of their close connection to the dynasty’s Manchu emperors. Yet, the banners also included a large number of Han Chinese; indeed, prior to the 1750s, Han had likely been the plurality of banner people. Holding banner status meant access to an array of privileges, from a guarantee of state financial support to reduced punishments for crime and vastly increased access to well-remunerated jobs in the Qing civil service. Zhao Quan wanted his son in the banners for the most basic of banner privileges: access to a position as a banner soldier, a job that in the years around 1800 was unlikely to require much actual fighting, but carried a substantial salary in both silver and grain.

Zhao Quan, however, was not just an ordinary commoner envious of banner privilege, but was himself a descendant of banner people. Beginning in the 1750s, the Qing court had sought to expel most Han Chinese living in provincial garrisons (that is, those not in Beijing or in Manchuria) from the banners. Where banner status had once been a privilege accorded to a multi-ethnic group of imperial servants — the soldiers and administrators who were the bulwark of the dynasty — the Qianlong emperor, who inherited the throne in 1735 and reigned for 60 years, had decided that Han did not truly belong in the banners. Though half the Han bannermen in Guangzhou had in fact been allowed to remain — making it the only provincial garrison that still had a large Han population after 1780 — Zhao’s father was not among them.

What Zhao did to support himself is unclear, but he certainly did not consider it enough to provide the sort of income he desired. As he told the interrogators who questioned him in 1813, “[when my son was born] I was a person expelled from the banners, with no means of support.” Luckily for him, though, his banner ancestry actually granted him connections within the Guangzhou garrison. His wife, who also must herself have been the child of Han people expelled from the banners, was the cousin of Hequan’s wife, surnamed Wang. Since banner people were forbidden from marrying commoners, Mrs. Wang’s parents were likely among the Han banner people of Guangzhou lucky enough to avoid expulsion, and her marriage to Hequan gave Zhao an opening. In late 1793, just after his son’s birth, he sent his mother to discuss the possibility of adoption with Hequan. Hequan quickly agreed, likely recognizing that the garrison’s shortage of Manchu personnel meant that any Manchu man was almost certain to be able to get a salaried post when he came of age. Hence, even if the income had to be shared with Zhao Quan, Hequan would have additional support in his old age.

To cover up the boy’s identity, it was necessary to give him a Manchu name, which is how he came to be called Quanheng. His original name had been Zhao Tianlu, a name which expressed his birth father’s plan for his life: the characters in his given name, Tianlu (添祿), literally mean “to add an official salary.” Zhao Quan and Hequan’s plan went smoothly for two decades. The rechristened Quanheng was falsely enrolled in the banner registers as a Manchu and Hequan’s own son, and received a small stipend from a supernumerary post even as a child, of which Hequan gave Zhao Quan about 25 liters of rice each month. Only when Quanheng was old enough to receive a regular position and a substantial increase in income, did Hequan refuse to share, leading Zhao Quan to reveal the arrangement to Quanheng.

The results were not happy for anyone involved. After rigorous interrogation, the banner and local government officials who investigated the case determined that Quanheng had genuinely been in the dark. It was still necessary to remove him from the banners and take away his cavalry post — he was, after all, still not a “real” bannerman — but beyond that he would not be punished. His two fathers met harsher fates. His adopted father Hequan, in accordance with the law on acquiring military provisions (that is, his adopted son’s salary) under false pretenses, was sentenced to spend 60 days in the cangue and then receive 100 strokes of the whip, a sentence that was only so light because, as a bannerman, the normal sentence of 100 blows of the rod and exile to Xinjiang was automatically commuted. Zhao Quan was less lucky, and “fell ill” after his confession was taken, likely as a result of judicial torture. He died in custody on July 26, 1813, never having been able to partake of the salary that he had plotted so long to obtain.

David Porter is a Ph.D. Candidate in History and East Asian Languages at Harvard University, focusing on the history of the Qing Dynasty. He is a 2016–17 Graduate Student Associate at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies.