Jane Zhang, MDes ’17 in Urbanism, Landscape, Ecology candidate at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, explores how food and changing tastes impact landscape in China’s Zhejiang Province. This essay received an “honorable mention” in the Fairbank Center’s 2016 Travel Essay Competition.

Since 1978, China’s rapid urbanization and cosmopolitanization have led to considerable and palpable environmental change. While policy responses tend to focus on urban and technological investments, however, the nation’s de-ruralization process is not subject to the same degree of questioning.

Cultivated landscapes and traditional food practices hold invaluable ecological knowledge that can inform both rural and urban sustainability strategies. By converging insights from landscape, food studies, and anthropology, I began researching local food products as a vehicle for land-based cultural memory.

This project, generously supported by the Fairbank Center’s summer funding, examines the case of the Stone Oak tofu dish to examine the idea of terroir and regional food. The preliminary research results confirmed the presence of terroir as a local concept, found a new sixth phase of nutritional development that combines Western with traditional food practices, and discovered ruralism to be a defining cultural trait of urban environments.

Since William Rees coined the term “ecological footprint” in 1992, quantitative carbon-based analyses have defined a primarily Western lens for studying and designing our built environments. Despite the land-based illusion of the footprint analysis, the metric is largely abstracted from geography.

Not all land is equal

The story of urbanization, geographically defined as the manifold processes of uneven spatial development, might best be told through the story of agriculture. In Massimo Montanari’s words, “the very creation of the city, perceived by the ancients as the place par excellence for the development of civilization would be inconceivable without the development of agriculture, either on a material level (the accumulation of goods, riches, technology), or on a mental plane (the idea that man becomes his own master and separates himself from nature by creating his own space in which to live)”.

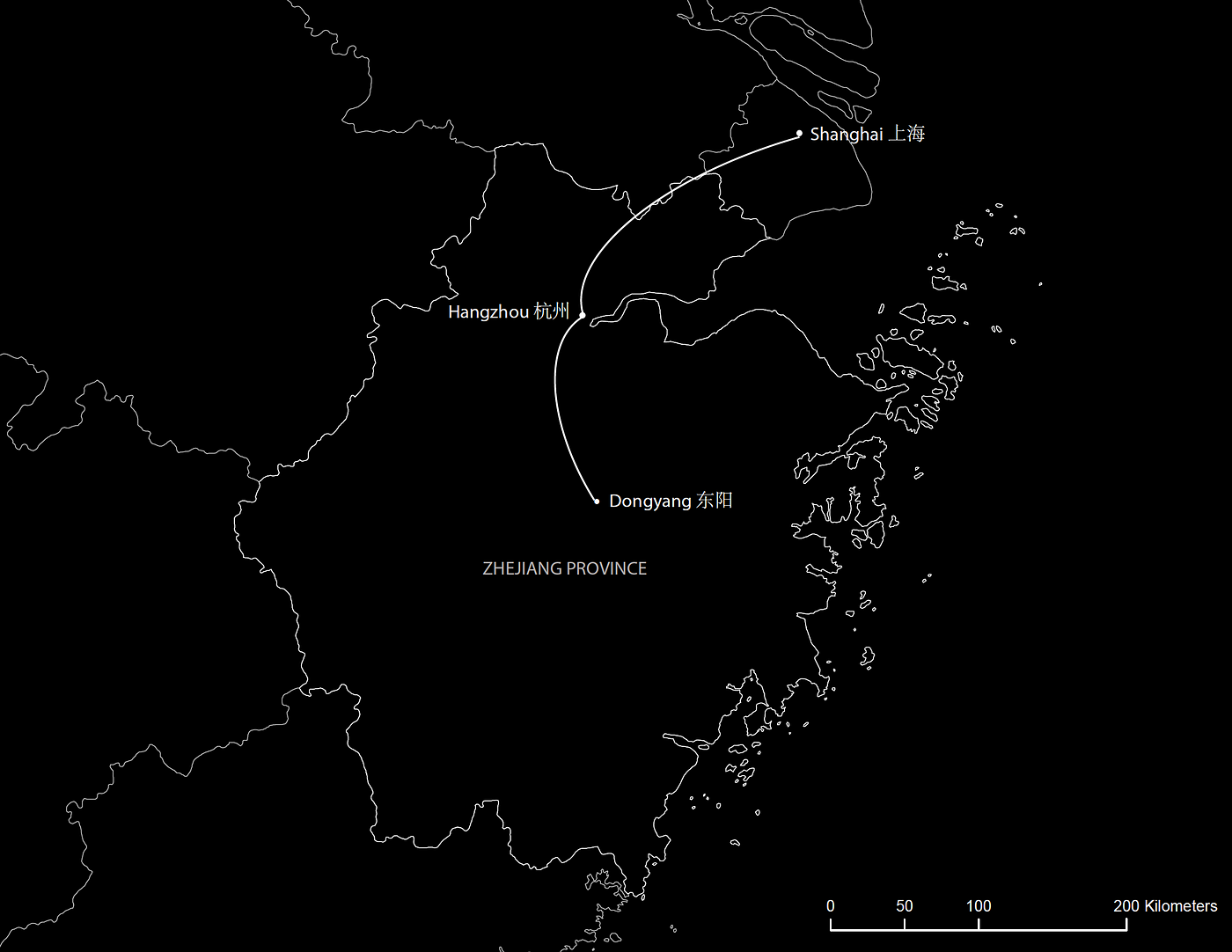

Viewing landscapes as living archives of human interventions, this project turns to Zhejiang, China as a site for defining urbanism through food. Contemporary China as a posterchild of solastalgia raises questions that technocratic instruments alone cannot address. If the Sustainability project is about ensuring the survival of our civilizations, why not turn to long-standing civilizations for guidance? As Nancy Turner and Helen Clifton (2009) argue, “These are people who are long-term residents of a place, who have learned through systems of knowledge, practice, and belief to conserve, maintain and promote their resources in situ, and who have developed a capability for resilience (a capacity to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change).”

Between 1985 and 2001, built-up land cover in Zhejiang province has quadrupled, with 90% of these areas formerly having been croplands. Since 1978, China’s national policies for industrialization and Westernization (and in turn urbanization) have disassociated millions of rural-urban migrants from their homelands and cultivation practices. While research across spatial analysis, public health, and environmental studies have described socio-environmental changes in piecemeal, this project begins to visualize, spatialize, and compile trends in literature with ethnography.

How can food culture, the practices of producing and consuming food, serve as a proxy for the changes in cultural systems and physical landscapes?

The European notion of terroir has come to describe the rootedness of particular a cuisine, produce, products, and recipes, to a specified region. While this concept has circulated widely in the West due in large part to the Slow Food movement, Montanari questions the historical authenticity of the concept. Since the Middle Ages, Europeans of all classes have desired a “universal banquet” over eating “geographically”. In fact, the terroir is more likely have been a response to nineteenth-century industrialization and globalization of food markets.

How does terroir manifest in Zhejiang today? What role do environmental and landscape changes play in shaping influence families’ dietary choices? How do changing diets, in turn, impact land use?

My research highlights a number of key questions regarding local food production, sustainability, and landscape: Might traditional or local foods play a role in the social and ecological sustainability of a region? If so, how might they do so without people having to dislocate desires?

Case study on Stone Oak Tofu

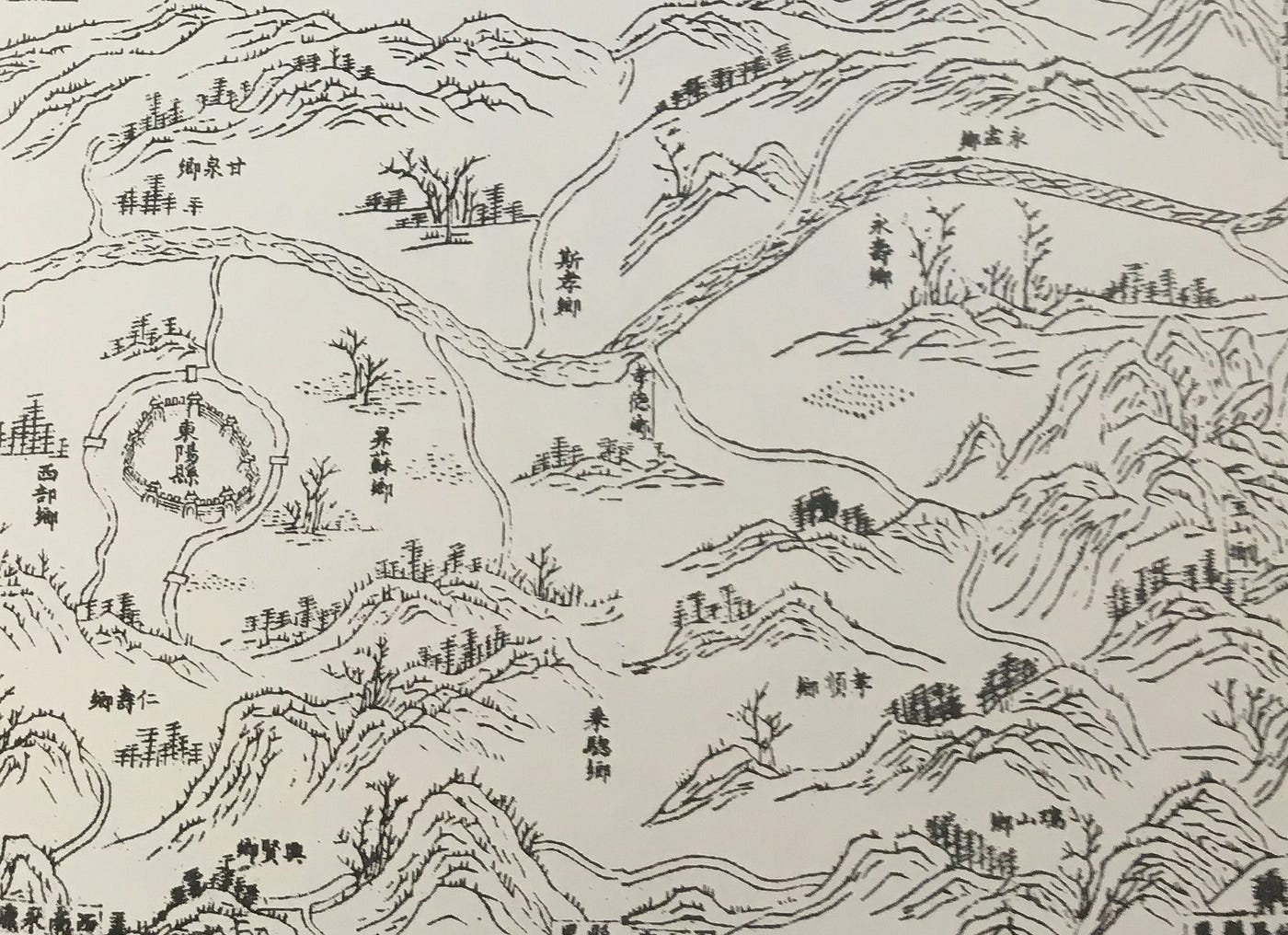

As a representative product of terroir, Stone Oak tofu is made of acorns from the Lithocarpus glaber plant, a wild oak species native to coniferous forests in low mountainous regions of eastern China and Japan. The acorns are foraged from these remote areas, dried, and ground into a flour to make a cold dessert dish. The plant’s ecological and biogeographical traits and the dish’s production process are documented.

To fill in the gaps between statistics and maps, I lived in Zhejiang for 38 days, eating and documenting dietary practices of local urban and rural relatives. My family ties to the province allowed me access to authentic local culinary experiences, as well as to archival documents.

Is there such thing as a “traditional food product” in Zhejiang? If so, how might these foods connect migrants to their geographies and histories of origin?

Beyond Acorns

While the tofu dish supports the idea of terroir and regionalism in Zhejiang, my fieldwork made me question the isolationist method of examining a single object. The project’s true goals are about drawing the ecological relations between people, their food, and landscapes across time.

The foregrounding of a single food item has often led to a superfood phenomenon, whereby demand by industrially developed markets for a single “miracle food” transform entire developing landscapes to re-route supplies. While Science tends to treat food items as clusters of cells providing particular benefits or ills, each food acts as unit of meaning in our cultural systems. In many Chinese homes, food serves as the core of familial care. As a guest, one is always welcomed by some form of nourishment; the summer heat is often alleviated by a slice of watermelon, a fresh pear, or a bowl of acorn tofu.

Generational Shifts

The palettes of palate offered by capitalism have shifted the tastes and material priorities of Chinese youth. Generation Y and Millenials prioritize ephemeral sensory experiences above nutritional value, and particularly value the aesthetic of foods, as evidenced by the mass amounts of food images on social media. While youth revel in the immediate satisfaction of colorful, heavily flavored, processed foods, one 53-year-old woman said the following about a sugary coconut drink: “We don’t drink stuff like that; it’s for the young people.”

Those born in and before the 1970s tend to favor home-cooked foods. Most are also extremely knowledgable about plants and agile with their hands — both in making foods and in creatively utilizing material for everyday needs. For many retirees, daily routines revolve around food: morning trips to the farmer’s market, washing vegetables, preparing meats, cooking, and then ensuring their progeny are well-nourished. Communal meals become daily highlights and mealtime chatter often revolves around the dishes — their quality, price, taste, and associated memories.

Ruralism is Everywhere

Chinese regionalism courses through contemporary geography by differentiating food practices and land use between regions. Each county, with its makeup of towns and urban centers, is known for its 土菜 or “earth (soil) dishes”. While rural-urban migration continues, many upper middle-class urbanites are beginning to purchase rural land for organic or industrial farming, though land rights are exclusive to local families.

While China’s eco-tourism and environmental policies privilege urbanites, the imprint of rurality abounds. Dongyang 东阳, essentially an urban agglomeration of its surrounding rural villages, gives new life to the idea of an urban village. Communalism and neighborliness seep through the growing thickets of concrete, glass, and traffic circles. While apartment towers rise as rapidly as trees re-inhabit rural mountains, migrants carry their rural practices to their new homes: fishing in urban ponds, growing vegetables in courtyards, sharing their bounty with neighbors and friends. Ruralism, like urbanism, does not necessarily denote a spatial typology or even land use. My fieldwork suggests ruralism to be a way of life — a deep understanding of material, attentiveness to physical processes, and a communal approach to time and resources.

Jane Zhang is an MDes candidate in Urbanism, Landscape, Ecology candidate at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.