Jinah Kim, Gardner Cowles Associate Professor of History of Art and Architecture, examines how an exhibition on Buddhist art at Beijing’s Palace Museum could establish the foundation for greater dialogue and understanding between India and China. This blog post first appeared in the Harvard University South Asia Institute’s “Faculty Voices” series, and has been lightly edited for the Fairbank Center blog by James Evans.

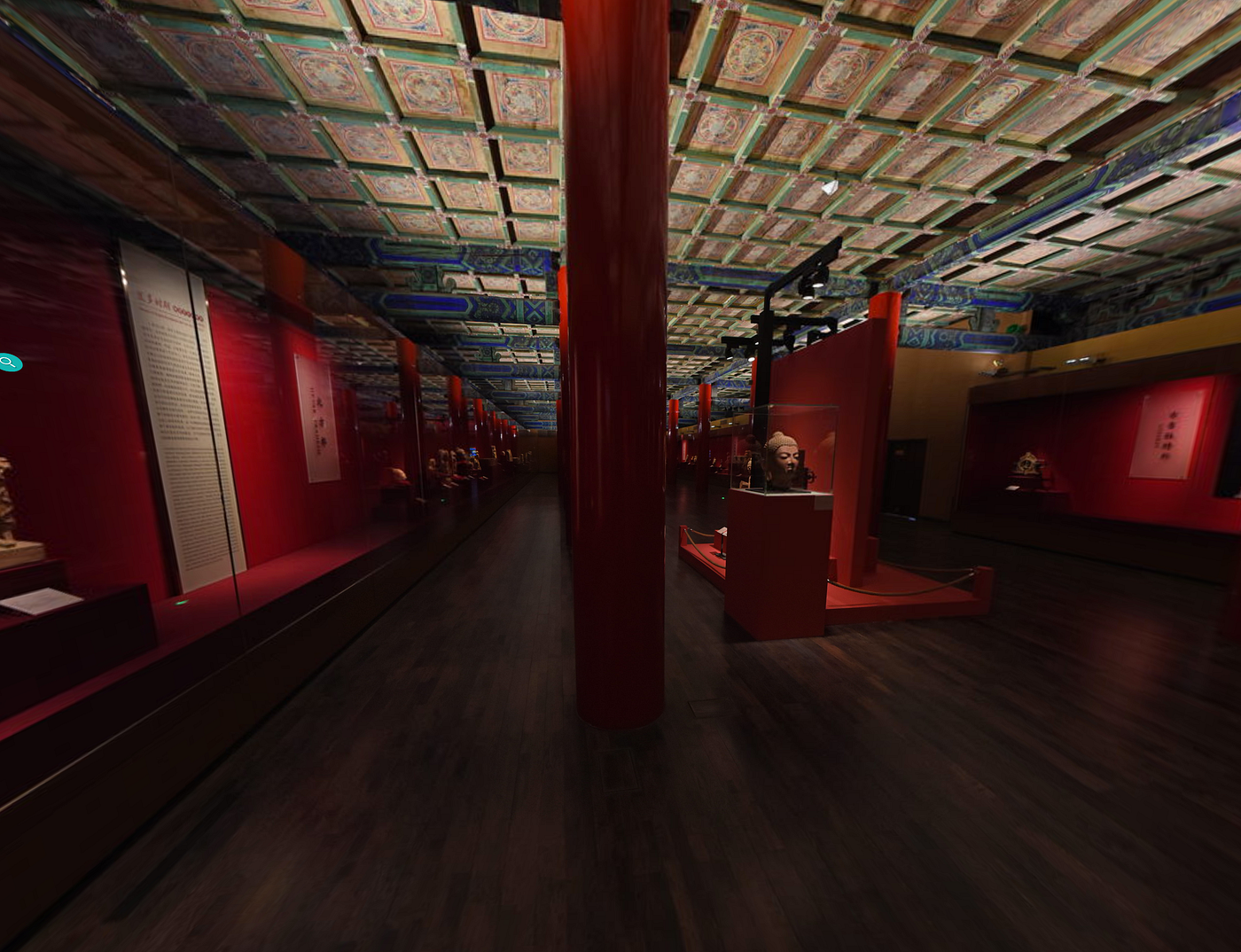

A first major loan exhibition of Indian art in Beijing was recently held in the majestic Meridian Gate tower of the Palace Museum of the Forbidden City (see a virtual tour of the exhibition here.) “Across the Silk Road: Gupta Sculptures and their Chinese Counterparts during 400 to 700CE” was an ambitious exhibition conceived by the senior curatorial fellow of the Palace Museum, Dr. Lou Wenhua, after his visit to India three years ago.

Fifty-six sculptures from nine Indian museums were on display against a red backdrop in one gallery, while two adjacent galleries were filled with over one hundred Chinese Buddhist sculptures against blue backdrop. Bringing this exhibition together was an impressive feat by the organizers in Beijing, which, of course, was not possible without collaborative efforts from many museum personnel and officers in India.

While the China-India bilateral relationship is not as rosy and warm as anticipated (i.e. India’s failed entry into the NSG at the Seoul plenary, as well as the China Pakistan Economic Corridor developments — part of President Xi Jinping’s Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Maritime Silk Road projects), the exhibition reminds us of the age-old connections between the two countries, notably activated and solidified through the transmission of Buddhism. It also opens up new possibilities for trans-regional connections in the future that may benefit tremendously from a mutual understanding of each other’s culture and history.

The time frame of the exhibition, from 400 to 700CE, is the period in which three Chinese monk-pilgrims, Faxian 法顯 (337-c.422CE), Xuanzang 陳褘 (602–664CE) and Yijing 義淨 (635–713CE), visited India. Their travelogues are enthusiastically mined as indispensable records for understanding the history of Indian Buddhism and the history of early medieval India, although they are at times unfortunately without any critical consideration of the Chinese monks’ own cultural prejudices and political motivations. The exhibition heralds “Gupta sculptures” as its main anchor perhaps unwittingly perpetuating a notion of the Gupta period (c. 320–550) as the “classical” or “golden” age of Indian Art, formulated during the early twentieth century. The selection is commendably wider in scope, however, in terms of the range of dates and the variety of iconography (from a circa third century Buddhist sculpture, to a circa fifth century Jaina stele, to circa seventh century Hindu sculptures).

The Palace Museum and the Forbidden City Cultural Heritage Conservation Foundation organized an international symposium to accompany the exhibition. I was invited to participate in it as an expert on Indian Buddhist art along with other foreign scholars from India and elsewhere (including the Fairbank Center’s Professor Leonard van der Kuijp). The three-day symposium was packed with speakers presenting on a variety of topics with about two thirds of papers on Chinese Buddhist sculptures of the period between 400 to 700CE. It was an exciting opportunity to learn about discoveries of new art historical materials from recent excavations.

On the India side, according to Dr. B. R. Mani, a respected archaeologist and the current director of India’s National Museum in New Delhi, a recent excavation at Sarnath, the celebrated pilgrimage site of Buddha’s first sermon, revealed material evidence for the hitherto-unnoticed existence of a sculptors’ workshop at the site. Many more new findings in China were shared with much enthusiasm and excitement. Chinese archaeologists seem to be discovering and excavating many more Buddhist sites and other related historical sites than ever before. The sheer amount of historical details and art historical evidence that emerge from these new excavations is incredible.

Close collaboration between archaeologists and art historians in the study of Chinese Buddhist art is something of envy for scholars working in India. A similar collaborative effort can lead to more fascinating discoveries and improve understanding of historical sites in India. Better coordination and centralized distribution of resources on this front will help the cause. It is a tall order, given the complexity of politics in center-regional government relationships in India, which partly accounts for the reduced number of sculptures that made to the exhibition: over 100 objects were initially chosen for the exhibition which appear in their glorious photographs in the hefty two-volume catalog of the exhibition, but only about half made it to Beijing.

This is not an insurmountable goal, however, especially with confident leadership among the heads of the archaeological, museological and academic organizations. While management of archaeological sites and cultural heritage falls under the purview of the government at both central and state-levels, inviting the private sector to contribute in improving public understanding of the past will open up innovative ways to create critical historical knowledge for the future. Moreover, promoting such cross cultural understanding can be mutually beneficial in the long run, as long as we remain mindful of pitfalls of unidirectional and hegemonic approaches that claim India as the origin of everything Buddhist elsewhere or those that treat India or China as a uniformed single cultural entity.

At the symposium in Beijing, a number of papers by Chinese scholars discussed Indian examples for comparison with the goal of ascribing an origin to the Indian examples for a style or an image type developed in China. Over the course of the symposium, it became clear that there exists a rather schematic understanding of Indian art in Chinese scholarship. By the same token, scholarship on Chinese Buddhist art by Indian scholars is nearly nonexistent and antiquated.

The exhibition in a way marks a point of departure for a new era of cross cultural exchanges and mutual understanding between India and China. One certainly hopes similar initiatives continue to come forward. A similar international exhibition in India would certainly spark much Indian interests in better understanding China’s history and art.