Sha Fei 沙飞 photographed China’s turbulent wartime in the 1930s and 40s, and in doing so defined a national visual culture. Curator Chiaomei Liu, Professor of History at National Taiwan University and TUSA Scholar at Harvard University, introduces Sha Fei’s life, works and artistic influences.

Sha Fei’s early work reflects his beloved memories from his honeymoon to Suzhou and Hangzhou in 1933. His reflections on this trip motivated his pursuit of unique visualizations throughout his photography career.

In 1935, Sha Fei joined the Black and White Photo Society, a pioneering modernist photographers association in Shanghai. Due to his involvement with the Society, his early semi-abstract landscapes were informed by prominent photographers’ works, such as Edward Steichen’s cloudscapes and Lang Jingshan’s photomontages.

Encouraged by the socialist writer Lu Xun, Sha Fei became a politically engaged photographer by publishing in magazines. In October 1936, he gained widespread recognition from his images of Lu Xun, in particular from two heliographic images of the writer on his deathbed. To promote woodblock prints and magazines as socialist media tools, Lu Xun had organized exhibitions of German expressionist woodblock artists, such as Käthe Kollwitz.

With a similar motive, Sha Fei’s views of fishermen on Nan’ao Island, Fujian, taken in the years 1935–1936, were published with his captions in 1936 and 1937, and thereby showcased the poetic waterscape of south China under threat of Japanese invasion from across the Taiwan Strait. Starting in August 1937, Sha Fei worked with the Nationalist government and moved to Taiyuan in the Chin-Cha-Chi Border Area with the staff of the Eighth Route Army.

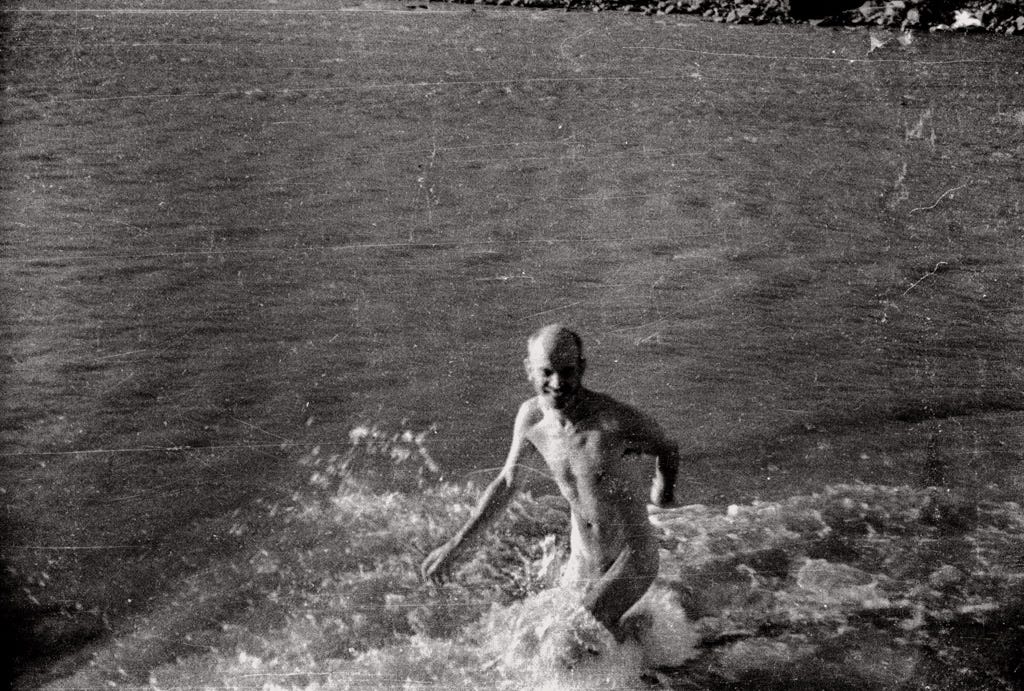

Having trained at the Shanghai Vocational Art Institute from 1936–1937, Sha Fei became versed in western art and had a penchant for pictorial composition. This can be seen clearly in his snapshots of the Canadian communist Norman Bethune, a medical surgeon, portrayed as a cosmopolitan figure splashing in a scintillating river or sun-bathing on a mountain ridge.

Sha Fei also documented peasants and workers in heroic postures set off by contrasting light and shade, similar to many modernist urban scenes. In particular, the image of the commander Nie Rongzhen with the young Japanese girl under his care (1940), viewed from a higher level, served the communist propaganda with a sense of theatrical character.

In Sha Fei’s wartime photojournalist documentaries (1937–1949), his signature framing of close-up shots of human figures within a segment of almost monotonous landscape often reemerged as film stills of revolutionary figures. Majestic views of man and nature were very prominent in Sha Fei’s work, such as in the mesmerizing photograph of three guerrilla soldiers under cover in a sorghum field, named the blue veil (青纱帐) on account of its unsettling thickness as camouflage under full sunlight in summer (1938).

Sha Fei’s photographs are on display at the Fairbank Center until April 24, 2016. A conference on Sha Fei’s photographs and their influence on China’s visual culture will take place from Friday, April 22 to Saturday, April 23.